Persea palustris

Lauraceae

Part of the fun of plant enthusiasms is witnessing the complexities embedded in the green world. A “hard look” at any given species flowering system often turns up more fun than the birds and the bees merely moving pollen from blossom to blossom, although that is mighty nice.

Swamp Bay

Swamp Bay belongs to the genus Persea, which claims also Avocado, Red Bay, and many additional species. Avocado and probably Red Bay have systems similar to the one that will soon awe you, differing in details. Its flowering program forces cross-pollination between two different strains within the same species.

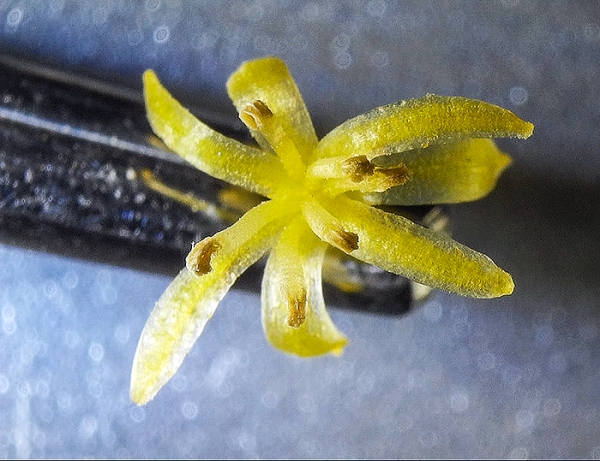

If you are wondering, the blue thread marks the flower as male in the early session.

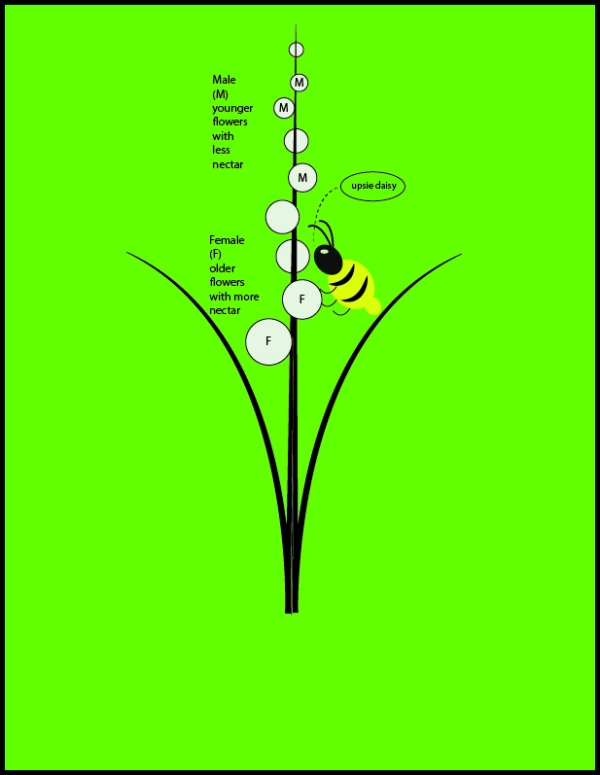

Now pay attention. This is mildly complex. The tree has two flowering periods each day: the first period is early afternoon, the second period is late afternoon-evening.

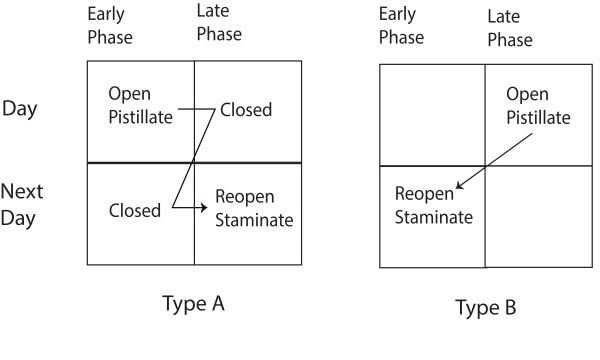

We’ll call the two strains Strain A and Strain B. Strain A opens its flowers in unison as temporarily female (pistillate) in the early session. At the end of the early session they all close and stay closed until the late session the next day. Repeat, they stay closed over 24 hours. When they re-open in the late session on the second day they have transformed from female to male (staminate), and release pollen.

Strain B, by contrast, opens its flowers synchronously as female in the late session. Yes, that is the Strain male moment, handily allowing Strain A to pollinate temporarily female Strain B. Strain B closes at sunset, to reopen transformed to male the next day in the early session. At that point the now-male Strain B can pollinate the then-female opening Strain A flowers.

Staminate = male. Pistillate = female.

Swamp Bay deviates infrequently from this pattern. Whether the exceptions are mere software glitches as opposed to being “meaningful” is unknown. The deviations may allow occasional beneficial self-pollination as assured pollination, let’s say in situations where the other strain is absent. A second possibility is that self-pollination or fruiting without pollination (it happens in many plants) may be common enough in Swamp Bay to allow the fancy system to “relax.” Nobody knows and I’ll bet nobody will know anytime soon. One thing for sure though, shifting back to Avocado, for a healthy crop you usually need a mix of the two strains close together, although they have their own deviations and many commercial Avocado trees can fruit without cross-pollination.

All that said, it boggles the mind how such a mind-boggling system with two blooming periods can force two different Persea strains to cross pollinate spanning two days. 2X2X2. I don’t think I could program that puzzle if I tried. But Swamp Bay is smart. And how do the two strains manage to be “all male” or “all female” in concert depending on the time of day anyhow?

Obviously past research is full of insights…duh. But there’s no substitute for personal experience. Here is homework. When you see a Swamp Bay or Red Bay in flower, jot down its sex (releasing pollen or not) and the time of day—early afternoon or late afternoon/evening. Or mark it with color coded thread. If the first check was early afternoon, check it for male or female at dusk a different day. Or vice versa. Like a “White Chocolate Tres Leches” donut, interesting on paper, but full marvel comes with the experience.